By Lee Cuesta

In 1953, a baby boy was born—weighing roughly 176 pounds (80 kilograms)—in the forests of India. Using their trunks, his mother and the other females assisted him to his feet so that he would begin nursing. He didn’t know yet how to use his own trunk. It dangled without purpose, and sometimes he tripped over it.

A few years later, this strong, young bull was full of exuberance and imagination. He was a free soul; he had no name because he belonged to no one. He enjoyed the dappled sunlight through the forest canopy, and relished the soft cushion of the jungle floor. His favorite foods were moist, tender roots and dark green leaves. Now his trunk was a mighty tool that he could wield with precision. His mother and “aunties” had raised him well, and in several more years he would begin his solitary life, or join together with a few other bachelors. When he was old enough, he would find a matriarchal herd in order to mate and reproduce.

Gajraj takes his first steps of freedom at the Elephant Conservation and Care Center.

But all of this abruptly changed. Suddenly one day he was captured. He heard loud explosions like he’d never heard before. The entire herd began to run in chaotic directions. He couldn’t keep up. His eyes expressed the terror and confusion he felt. What was happening? Where was his mother? He wanted to protect her, just as she had protected him many times.

Capture and Training

Kartick Satyanarayan, co-founder of Wildlife SOS in India, confirms the plausibility of this scenario. During a recent interview via Skype, he told me: “The poachers for live elephant trafficking try to target herds where there are female elephants with very young calves. If they have very young calves, they cannot move very far because the calves cannot walk long distances, and their speed is very limited. So the herd moves very little. The aunts and the mother actually look after the calves; so they move a few kilometers, and they wait there, near a water hole or something. Their movement is rather restricted. So then, the poachers target those herds, and they try to use both firecrackers and loud sounds to drive the herd in a direction where they get separated from the calf. The calf falls into a pit because he’s not able to keep pace with the rest of the herd. So then they can steal the calf and separate it, and harvest the calf out of that herd, and move away. Of course it leaves the complete herd distraught, highly traumatized. And the calf is also traumatized by being separated from its mother at such a young age.”

Now they gave him a name. This strong, young bull was no longer free; he belonged to humans. With cruel irony, they called him Gajraj. “His name means ‘The King of the Elephants,’” according to Nikki Sharp, Executive Director of Wildlife SOS in the USA.

Kartick continued: “Then these little elephant calves are put through a very brutal, painful, and barbaric process of training.” The owners tie them up and beat them to teach the calf who’s boss. The trainers often use spears and sharp objects, and keep the calf chained for several months on end, on hard concrete in order to have the spirit broken, Kartick explained. “And once the spirit is broken, then the animal is trainable and ridable.”

He added: “When people want to buy an elephant—illegally—they place an order, and then somebody causes the elephant calf to be poached from the wild. And then that elephant calf is tied up in the middle of the jungle somewhere, in a hidden location, beaten for several months, and in about a year it’s trained to do certain, basic things. Then it’s sold off. Wherever it goes, they subject it to further training, which means further cruelty and pain and suffering.”

Spiritual Significance

So Gajraj became a temple elephant. Kartick said, “And a lot of the public who are devotees or temple visitors, who have faith in these temples, do not understand what is the background of the elephant. They want a blessing from the elephant, but do not understand that even for the elephant to lift its trunk and give them a blessing, it’s been trained to do so through a very cruel and painful process. Everything is negative reinforcement only, and there’s only two tools that are used in the traditional methods of management in India to train Asian elephants, and that is pain and fear.”

Gajraj was sent to Ujjain, an ancient city beside the Kshipra River in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. An important Hindu pilgrimage destination, the Bade Ganesh Temple is located there, which houses a colorful statue of Ganesh (or Ganesha), the elephant-headed Hindu deity. When I asked Kartick about the spiritual significance, or value, placed upon the elephants in India, he replied: “Ganesh is our elephant god, and he is the god of good beginnings. He’s got a human body and an elephant’s head. He can have four, eight, and two arms—sometimes even more. And in each of those arms he’s probably holding something, or he’s holding it in a certain position; that indicates something spiritual or religious. Most people in India believe in Lord Ganesh, at least all the Hindus do. And they think that the elephant itself is an embodiment of that god.”

Kartick continued: “A lot of temples try to get an elephant into the temple, and keep it there, captive, because then it adds to the value of the temple, increases the visitation to the temple, and also increases revenue to a certain extent.” Kartick agrees that it’s a total contradiction to view the captive elephant as the embodiment of the god, and yet treat it so cruelly and inhumanely.

Then in 1965, at the age of approximately 12 years, Gajraj was given as a wedding present to the Queen of Aundh on the day she married King Bhagwant Rao. So he was made to travel 800 kilometers from Ujjain to Satara, Maharashtra, which took almost a month and a half, according to hindustantimes.com.

As the god of good beginnings, Wikipedia states, Ganesh is honoured at the start of rites and ceremonies, and so as a wedding gift, Gajraj represented a tremendous blessing upon the marriage. Wikipedia also calls Ganesh “Obstacle Remover.” A statement from Wildlife SOS says, “Gajraj played a vital role in the celebration. Ever since, the elephant has been a star attraction at the temple of Aundh, playing an important role during annual festivities and temple processions. Temple devotees see Gajraj as an icon of worship, as explained in the words of the Queen herself.”

Gajraj in captivity at Aundh prior to his retirement.

Care During His Captivity

“Often, people offer sweets and other artificial snacks to the elephant to seek blessings. However, for Gajraj, it is no blessing but a curse, as such foods can cause intestinal complications as well,” said PETA’s India director of veterinary affairs, Dr. Manilal Valliyate. Members of PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals) found Gajraj chained near popular tourist spots like the Shri Bhavani Museum and Yamai Devi temple in Aundh, Satara, according to hindustantimes.com. “Being chained for most of his life has had a detrimental effect on Gajraj’s health. He has lost weight and has nutritional deficiencies,” said Dr. Yaduraj Khadpekar, senior veterinarian with Wildlife SOS.

During his half century in captivity, “standing on unnatural surfaces for long periods of time has led to Gajraj’s footpads wearing out, which can be exceptionally dangerous for an elephant – making him prone to developing wounds and abscesses underfoot,” states a report from Wildlife SOS.

In addition, according to a statement from Save The Elephants, “Gajraj’s tusks have been chopped over a period of time without taking any permission from the forest department under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.” Kartick commented: “I am not sure of the details of what happened to the ivory, but I do know, I can see—it’s quite visible—that he has had his tusks chopped off.”

His chopped tusks are visible in the photos that accompany this article. The redness that appears at the ends of his tusks is not an injury, but instead the color of vermilion, which is red paint that was applied by the villagers because he was a temple elephant. Nikki Sharp told me that “what appears to have happened with this particular elephant is that his tusks were growing and criss-crossing; so he wasn’t able to lift his trunk up. So actually, they were doing the right thing; they shortened the tusks so he could lift up his trunk. But I’m not sure if they did it in a humane way or not.”

According to hindustantimes.com, “Gajraj developed partial blindness and a toenail abscess which could spread to the bone. He also has abscesses in the hip and his foot pads suffered severe degeneration. In April this year, the state government-appointed veterinarians said that the elephant was suffering from weakness and untreated prolonged abscesses on his hindquarters and elbows, as well as other painful foot conditions, and that his custodian had failed to maintain basic health-care records.”

Retirement for a Geriatric Elephant

Gajraj entering the Wildlife SOS Elephant Ambulance in July.

For these reasons, Gajraj was taken to the Elephant Conservation and Care Center (ECCC) in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, near Agra. This occurred last month (July, 2017), with permission from the royal family of Aundh. The royal family did not protest against any of the removal operation. In fact, they bid Gajraj farewell. “I am happy that the elephant is going to the rescue centre and I am confident that he is in safe hands,” said the Queen of Aundh, Gayatri Devi Pant Pratinidhi (according to hindustantimes.com). The ECCC is a collaborative project of Wildlife SOS and the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department.

“Gajraj was seen as a religious icon by local devotees, but his removal won’t necessarily cause disruption in the community’s cultural and religious fabric. The temple still exists and so do their religious beliefs,” stated a spokesperson from Wildlife SOS. “Gajraj (is) suffering from severe ailments and in need of expert veterinary care. The royal family of Aundh willingly handed him over to us for lifetime care as they understood that it was in his best interest to do so. Gajraj was with the royal family for decades and he is still very precious to them; so it is unlikely that he will be replaced by another temple elephant.” In a way, their relinquishing of Gajraj was a convenient way for the royal family to extricate themselves from an escalating liability.

“With advancing age, Gajraj was found to be suffering from several medical issues like foot and hip abscesses, severe degeneration of foot pads and partial blindness, making him a candidate for geriatric lifetime care. The Wildlife SOS Elephant Conservation and Care Center is equipped with veterinary facilities for elephant treatment and is currently providing lifetime care for over 20 rehabilitated pachyderms. Gajraj can now live a retired life for the rest of his life; however long his geriatric body can support him,” according to a statement from Wildlife SOS.

There is some disagreement about Gajraj’s actual age. A press release from Save The Elephants calls Gajraj “a 63-year-old ailing elephant.” The writer of a Hindustan Times report is confused: in the first paragraph, the reporter states that Gajraj is “a 70-year-old male elephant;” yet in the next paragraph writes that in 1965 at the age of 12, he was given as a gift to the queen at her wedding—which places the current age of Gajraj at 64 years. Kartick told me, “Our assessment of Gajraj is that he looks like he’s between 70 and 75 years old.” Either way, this bull elephant is close to the end of his life, with lots of health concerns.

“PETA did a good job with getting the story out there and letting people know about what was happening with that elephant,” Kartick said. “So we’ve had thousands of emails and requests asking us to step in and help. So when the Forest Department finally got to us and asked us if we could help, we did.”

How hard is it to remove an elephant from a temple? Kartick replied: “It can be excruciatingly painful and challenging, and can be extremely dangerous because contrary to what many people think, a lot of the Indian public is largely ignorant about what happens to an elephant before it becomes a temple elephant. They do not understand that every single elephant in a temple has actually been removed from the wild, separated from its herd as a little calf. And then these little elephant calves are put through a very brutal, painful, and barbaric process of training.”

Now Gajraj safely resides at the ECCC in Mathura. Baiju Raj, Director of Conservation Projects for Wildlife SOS, stated: “It is a tremendous responsibility to take care of a geriatric elephant like Gajraj. We will provide him the best of care.” Geeta Seshamani, co-founder of Wildlife SOS, said: “Gajraj will be provided long-term medical treatment and lifetime care at the hands of our experienced team at the Elephant Care Center.”

Gajraj takes his first dust bath at the ECCC in Mathura.

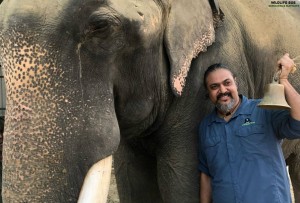

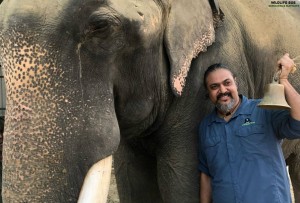

Kartick added: “Within a few short minutes of stepping into the centre, we could see a marked change in the behaviour of the elephant. He immediately took to the new surroundings, gorging on fruits and taking dust baths.” In a July 24 update, Wildlife SOS reported: “Last week we held a ceremony to remove Gajraj’s bell as a symbolic way to complete his journey to our Elephant Conservation and Care Centre (ECCC) in Mathura, ushering in his retirement and fully closing the circle on his previous life.” In a photograph, Kartick smiles for the camera after removing the bell.

Kartick smiles after removing Gajraj's bell.

Soon Gajraj will once again enjoy the dappled sunlight through the forest canopy, and relish the soft cushion of the jungle floor. Of course, it will remind him of his abbreviated childhood in the forests of India, so many years ago. According to a statement from Wildlife SOS: “After his initial period in quarantine, Gajraj will soon start going out on walks with his mahout, and get a chance to explore the sights and sounds of his new home beyond his spacious enclosure. This couldn’t come at a more perfect time, with the rains just beginning in Mathura, and the elephants’ walks covering a vast expanse of lush green vegetation, and an array of exciting flora and fauna for Gajraj to discover and investigate! While the concerns regarding the condition of his feet might keep Gajraj from going on long walks immediately, we know that when the time comes, he will take as much delight in the free space to roam and wander just as much as all our other elephants do.”

Gajraj entering his pool.

Meanwhile, Gajraj has discovered the joy of his very own, private pool in which he can lounge and relax. “Although he was initially wary about entering the water, we eventually managed to coax him in with bananas and muskmelons, and once inside, he was quick to realise just how wonderful it feels to be completely submerged in the pool – not just because the water is cool and soothing, but because of the weightlessness he probably experiences that takes the strain off his legs and extremely worn out feet,” states the Wildlife SOS website. In addition, the vermilion on the ends of his tusks has gradually washed away as a result of these baths.

It continues: “Gajraj is still getting a large amount of the staple diet he was used to in captivity – sugarcane – and we are gradually introducing other varieties of fresh green fodder crops into his diet. He also gets a delicious array of seasonal fruit including mangoes, watermelon and bananas, as well as corn and pumpkin. Gajraj has been prescribed nutritional supplements by our vets that he receives daily to complement his diet and promote his recovery.”

Furthermore, the ECCC staff is “introducing him to the safe and humane process of target training which will in the future allow us to easily treat Gajraj’s feet and carry out a host of other treatments with his happy and willing cooperation. Gajraj is an extremely smart elephant and has taken quickly to the basic stages of target training, so we’re proud to say that we can see him progressing pretty fast in his training – which will soon make it much easier for us to treat the abscesses under his feet.”

A Legacy for the Future

The retirement with the royal family’s permission of one geriatric elephant—and his relocation to a sanctuary—may seem to have little, or merely symbolic, significance. But Gajraj represents an elephant population that faces extinction, and the young ones continue to be poached for live elephant trafficking. “So basically, if you look at the whole world, we’ve lost 98 percent of the wild population of the Asian elephants,” Kartick stated. I asked him, “Do you think that it depends upon this generation or the next to prevent their extinction?”

Kartick responded, “Absolutely. It is really this generation or the next that can do something if there is to be hope. Otherwise, in five years, we could have no elephants. Our children and grandchildren might have to be shown elephants on photos and videos and Youtube, and there wouldn’t be any elephants left in the world. That is not a distant chance; it is a very real possibility if we are not careful.” He added, “It is frightening and it shows how much on the edge we are, and it’s a very fragile system and a very fragile state for this planet and for its denizens.”

While Wildlife SOS is not in the business of collecting elephants, as Kartick says, but rather in the business of educating the public concerning conservation for multiple types of Indian wildlife, they are buying land for the sanctuary to accommodate more elephants that they rescue. “Yes, we are in the process of doing that, and it such an uphill battle,” he said.

The land will cost over 1.7 million dollars, and so far, they have raised half that amount with contributions. I asked, do you need additional funding? He replied, “Absolutely; it is a tall order that we have. We have to raise a lot of money in order to make this possible. So if your blog can incorporate some of this and help us attract some investors, because this is a social investment. If people come forward and understand that we would all live a life, and we would consume and consume and consume all our lives, reproduce, and then die, and be gone. But we will not leave anything behind if we go at this rate. So we really need people to come forward and join us in making this a legacy for the future.”

-30-

Permission is granted to reprint this article in its entirety with the condition that its source (this website) and its author (Lee Cuesta) are both acknowledged.

(All photos are used by permission from Wildlife SOS.)

(Note from Lee Cuesta: I am offering this light-hearted guest post amid this temporary national emergency with the intention that it might bring some humor and levity to your periods of self-isolation and social-distancing. As noted at the end, you have my permission to reprint this in your publication or on your website if you’d like a short, humorous piece for your audience.)

(Note from Lee Cuesta: I am offering this light-hearted guest post amid this temporary national emergency with the intention that it might bring some humor and levity to your periods of self-isolation and social-distancing. As noted at the end, you have my permission to reprint this in your publication or on your website if you’d like a short, humorous piece for your audience.)